To keep its software applications applicable and profitable, a business organization is expected to optimize the user experience continuously. This user experience is usually determined by the specific software application’s functionality, usability, performance, security, and accessibility (Canfora et al., 2006). Legacy systems, unlike the new age systems, are not made to target multiple browsers, devices and operating systems to optimize the user experience. By definition, legacy systems are IT systems that are ominously resistant to changes and evolution (Bisbal et al., 1999).

Generally, they are any components, including hardware and software, pertaining to old and obsolete computer systems. To remain operative or competitive in the business world, enterprises have to take action to improve the user experience (Canfora et al., 2006). This means they have to have new-age technologies in place. The service industry like the banking sector, for instance, has to have the most current technologies to be able to give their customers a better user experience that would, in turn, translate to increased profits for these organizations. This paper will focus on how the implementation of up-to-date technologies in the banking sector is likely to be affected by the presence of legacy systems in similar or other parts of these organizations.

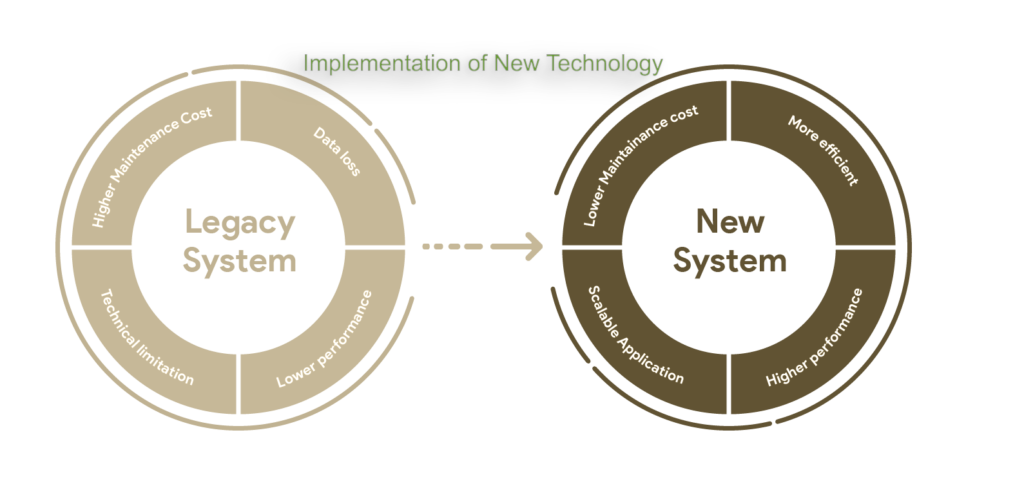

How Implementation of New Technology Is Affected By the Presence of Legacy Systems

Banks tend to keep their legacy systems for a relatively long time because these systems have been enormously effective and extremely reliable for decades now. As a result, many of the bank executives tend to reason that the problem is not with the legacy systems, but with the tools and technology that get wrapped around these systems over the years (Bisbal et al., 1999). Even if most of the legacy systems found in the banks is not compatible with the new technologies, the main payment processing systems within the banks have proved to be very effective. The issue is that the systems, software, and technology that have been developed over time tend to be quite different (Millard et al., 2006).

The difference in this case then creates problems whenever there is a need to adopt new technology, and this creates conflict between those who support innovation and those who are only interested in ensuring the stability of the bank. This conflict becomes more pronounced whenever banks try to go for digital strategies in which the technology that previously played only a supporting role is being adopted as part of the bank’s strategy.

Technology can be viewed from two perspectives. It can be perceived as a necessary evil, and a chief information officer (CIO) hired to help in keeping the costs down or as a strategic differentiator and a chief technology officer (CTO) or chief digital officer (CDO) hired to help direct the fundamental changes towards the direction that technology is being deployed or developed. In the same way, a digital strategy can be implemented in two ways. First is to adopt incremental changes process by process and system by system, gradually bringing people along. The other way is to adopt it all at once by undertaking radical changes.

Additionally, the digital strategy can be implemented from within, or a different entity can execute the radical change. Any of these approaches would work, but they would operate on immensely different velocities and cause disruptions of varying magnitudes (Bisbal et al., 1999). While such big technology companies like Amazon, Facebook and Google have been less burdened by the legacy infrastructure and are in a better position to adopt digital change, big banks are still primarily run on legacy systems hence the radical changes towards a digital age have remained more challenging.

Issues Involving Legacy Systems in the Banking Sector

Banks are cognizant of the fact that for them to survive the increasingly competitive business environment, they have to innovate. In many other sectors, companies are anchored on digital ecosystems so that their services are delivered digitally. Even within the banking sector, the new entrants tend to build new technologies from scratch so that they are in a better position to provide digital services to their customers in an enhanced way. In recent times, the regulators have been pushing the financial organizations to become more innovative. In the European Union, for example, the Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) and the open banking concept pushes banks to avail their customer data to third parties, which includes the rival banks and the new non-bank competitors (Romānova et al., 2018).

The concept is expected to bring tremendous change to everything within the payment’s industry including the way payments are made online and the information that the customers will see when making payments (Romānova et al., 2018). Contrasting, most banks appear to be still in the analog world, tied to their main banking systems, most of which are invariably obsolete legacy products, covered in layers of middleware and incompatible with the new digital technologies. Additionally, many banks have large internal IT departments that are historically tasked with developing a one-off system for these banks but have progressively found themselves extended as a way of ensuring the banks remain operational.

Banks have to this far, been able to retain their position as the leading financial service providers because of their long-established status as dependable institutions when it comes to handling the financial assets of their customers. If things remain the way they are, the banks risk being dislodged from their position by new entrants. Today, new digital-only banks that are anchored on lean and clean infrastructures are experiencing fast growth in terms of market share. The advent of open banking will most certainly erode the standing of the incumbent banks even more (Brodsky & Oakes, 2017).

This concept may as well work to the advantage of the existing banks should they undertake to increase their innovative efforts to keep up with the technological changes. The approach that these banks adopt will determine whether they will succeed in the competitive business environment or not. Again, most business organizations including banks, have most of their investment applications written in COBOL (VanLengen & Haney, 2009). More successful organizations are today doing away with COBOL programs and adopting more current languages like Java. To keep up with the pace, banks will have no alternative but to consider this change.

COBOL Illustration

Common Business-Oriented Language (COBOL) is an example of the legacy systems, and it is the very first popular language that was designed to be used for system-agnostic, mostly for business applications. The language is still widely sued for business and financial applications. This computer language was purposely designed for use in human resource and finance industries such as banks and other financial institutions. COBOL ordinarily use English words and phrases which make it much easier to understand for the ordinary business users. The figure below is an illustration of a system that uses COBOL language.

You may like to read this

The CNSS security model. How would you address them in your organization?

The role of centralized and decentralized IT operations on the implementation and maintenance of specialized information systems

Potential Points of Friction between Specialized IT Tools and Legacy Systems

The presence of legacy systems in the banking sector is a significant impediment towards the implementation of newer and more current technological applications. Today, banks are under intense pressure to adjust to the digital age and to go for more innovative approaches when it comes to product development (Cherukupalli & Reddy, 2015). This pressure is even more in the retail and transaction banking section in which there is a reinvention of the business model for the payment services. In the current digital age, communication, commerce, and all the other consumer services are digitally delivered.

There are, however, a few exceptions like in the case of banking, where some of the most advanced banks have not fully migrated into the digital age, mainly because they are still tied to the age-old baking and payment systems. In as much as these systems may appear to be critical to the operations of these banks, they are mostly incompatible with the digital services and the new generation digital applications (Cherukupalli & Reddy, 2015). The resulting situation has brewed crippling tension between the IT and business divisions within these banks. It is the situation where the business wants to innovate but the IT division is focused on maintaining the status quo. At the center of this tension are the legacy systems upon which the bank infrastructures are built. Being more innovative generally implies doing away with these legacy systems and adopting new technologies.

Banks are justifiably hesitant to replace the legacy systems because of the catastrophic consequences that may follow should the project fail along the way. Legacy system replacements have been marred by failures in several other sectors (Millard et al., 2006). Banks have been known to be reluctant to undertake sweeping structural changes, and if they are to pursue innovation, then they will need to have in place a strong leadership that will be fully committed to these changes. Shining up a legacy system and trying to make it appear modern with a new coding would not help as much.

At the same time, making too many radical changes all at once may prove to be catastrophic (Millard et al., 2006). Migrating from the legacy systems into the digital age needs to be done in an extremely controlled way by using a road map. To be able to implement new technologies appropriately, banks should first evaluate their existing IT landscape and make decisions on what needs to be retained, what should be replaced, and how the replacement should be done. All these will only be accomplished through proper insight and planning.

Conclusion

The banking sector is yet to migrate to the digital age, and the use of the legacy systems is still the order of the day. Adopting new and current technology by banks has been greatly hindered by the presence of these legacy systems. In as much as banks are under intense pressure to adjust to the digital age and to go for more innovative approaches when it comes to product development, the legacy systems present in these institutions are mostly incompatible with the digital services and the new generation digital applications, which cripples their implementation.

Additionally, the replacement of legacy systems has resulted in severe failures in other sectors, and banks are still not ready for the possible catastrophic consequences of replacing the legacy systems should the project fail. Generally, banks are primarily run on legacy systems. Therefore, any radical change meant to bring in new technology will have proved to be a challenge and the big banks are not ready to face these challenges yet.

Reference

Bisbal, J., Lawless, D., Wu, B., & Grimson, J. (1999). Legacy information system migration: A brief review of problems. Solutions and Research Issues.//IEEE Software, 16, 103-111.

Brodsky, L., & Oakes, L. (2017). Data sharing and open banking. McKinsey & Company.

Brune, P. (2018). A Hybrid Approach to Re-Host and Mix Transactional COBOL and Java Code in Java EE Web Applications using Open Source Software. In WEBIST (pp. 239-246).

Canfora, G., Fasolino, A. R., Frattolillo, G., & Tramontana, P. (2006). Migrating interactive legacy systems to web services. In Conference on Software Maintenance and Reengineering (CSMR’06) (pp. 10-pp). IEEE.

Cherukupalli, P., & Reddy, Y. R. (2015). Reengineering Enterprise Wide Legacy BFSI Systems: Industrial case study. In Proceedings of the 8th India Software Engineering Conference (pp. 40-49). ACM.

Millard, D. E., Howard, Y., Chennupati, S., Davis, H. C., Jam, E. R., Gilbert, L., & Wills, G. B. (2006). Design patterns for wrapping similar legacy systems with common service interfaces. In 2006 European Conference on Web Services (ECOWS’06) (pp. 191-200). IEEE.

Romānova, I., Grima, S., Spiteri, J., & Kudinska, M. (2018). The Payment Services Directive 2 and competitiveness: The perspective of European FinTech Companies. European Research Studies Journal, 21(2), 5-24. VanLengen, C. A., & Haney, J. D. (2009). Creating web services for legacy COBOL. Information Systems Education Journal, 7(28), 1-10.

Like!! Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.